Recently, my mom received a call claiming to be a “provincial public security satisfaction survey.” She didn’t answer the first two times and only picked up on the third attempt. She even called me to ask if it was a scam. As a legal professional, Old T was aware of such things. A few years ago, while taking my child to the hospital for a check-up, I was also “surveyed.” But undoubtedly, this kind of opinion polling seems like a “rarity” in China. Compared to the frequent poll data seen in foreign news, the presence of such surveys feels much less noticeable. If not for these two “survey” experiences with my family, I wouldn’t have known such “polls” existed domestically.

What Does It Feel Like to Be “Surveyed”?

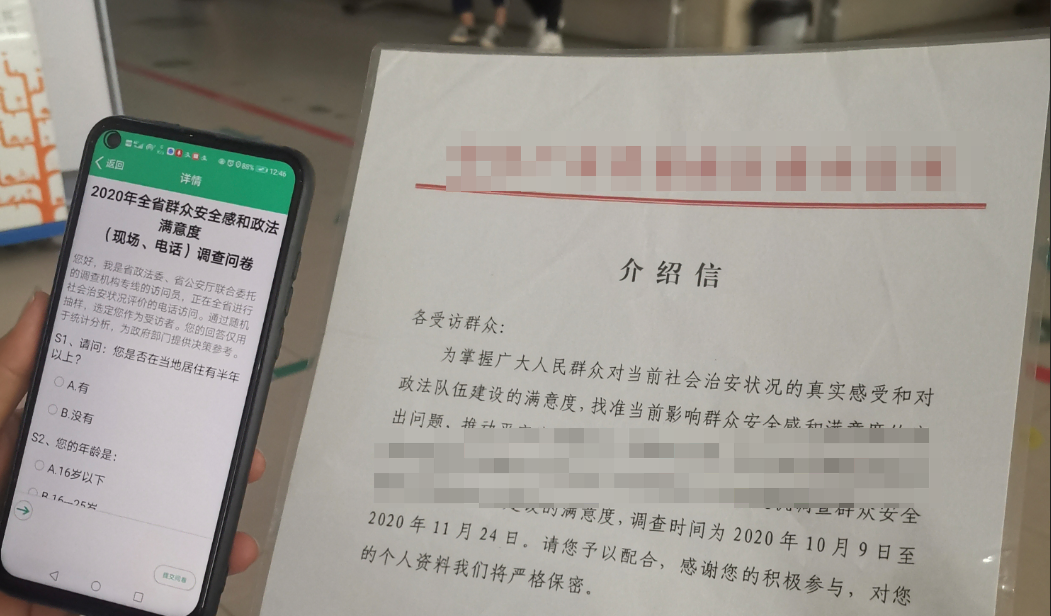

Old T dug up a photo from my phone album taken during that 2020 “survey” and recalled the experience. What stood out most was the interviewer first introducing themselves with a laminated letter of introduction.

This kind of laminated letter was something Old T had only seen before in train stations or on trains—people who looked no different from anyone else, holding a crumpled, laminated piece of paper, shoving it in your face, then gesturing to indicate they were deaf-mutes begging for money. At first, Old T gave them five or ten yuan, but after seeing it so often, it started to feel highly suspicious. Eventually, I adopted a policy of simply “ignoring” them. But honestly, the experience is morally taxing. You’re never sure if it’s genuine, and if the person really needs help, does your “ignoring” them leave a moral stain? Especially since these “beggars” usually wait in front of each person for ten to twenty seconds before moving on to the “next target”—those seconds are enough to make you feel uneasy.

Of course, maybe Old T was overreacting. After all, it’s been years since I encountered such “beggars,” and laminating documents is actually quite normal. If you carried a plain A4 sheet around every day for surveys, it would likely be worn out quickly, so laminating it is a practical measure.

Still, that survey left Old T with a lingering question. It was conducted via a mobile questionnaire—the interviewer asked a question, I answered, and then she input my response. I suggested, “Why not let me hold the phone? I can read and tap the answers myself—it’d be faster.” But she refused, saying it violated the procedure. This puzzled Old T for a long time. Wouldn’t answering myself better reflect my true opinion? If I say A and you enter B, doesn’t that distort the “true public sentiment”? Every time I thought about it, it seemed odd. Only today did Old T finally figure it out.

Why Do We Rarely Encounter Polls?

If you follow foreign news, it’s hard to miss the constant stream of approval ratings, satisfaction scores, and all sorts of opinion polls—it feels like they’re conducting surveys over the phone every day. In contrast, receiving a legitimate polling call here is such a rarity that you might talk about it for ages. Delving deeper, Old T thinks the reasons are quite complex.

First, the historical development of “polls” is different. Take Gallup polls in the U.S., which started in the 1930s—nearly 90 years of evolution have made them a staple of American political and economic life, and people are used to them. In China, while survey activities have existed for a long time—like the famous Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, which was essentially compiled through firsthand, village-by-village fieldwork—large-scale social surveys akin to Western ones only gradually developed after the reform and opening-up era.

This leads to the second key point: Who conducts the polls? Most domestic polling agencies are closely tied to statistical departments or Party and government bodies, with very few completely independent third-party organizations. This contrasts sharply with the proliferation of independent polling firms in the West. It means that even when surveys are conducted, they often have official backing and focus on government-related topics. Unlike abroad, where all sorts of quirky social issues might be polled.

Lastly, and most practically: We ordinary folks are too wary. Think of my mom’s reaction, or our own—when we see an unknown number, isn’t the first thought “sales call or scam?” Hanging up is the standard response. In such an environment, the answer rate for polling calls is predictably low. Sometimes the government even has to issue notices, earnestly pleading, “Don’t hang up on ‘12304’—we’re a legitimate survey!” But honestly, how many people does that reach? So, it’s not about “bad luck” in not receiving calls; it’s that the system itself isn’t well-integrated with our daily lives.

Why Didn’t the Interviewer Let Me Touch the Phone?

Returning to Old T’s initial confusion: Why did the interviewer insist on inputting the answers herself instead of letting me fill out the questionnaire directly?

After looking into it today, I understand it’s tied to the core issue of poll “accuracy.” The method they use is called “Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing” (CATI). In theory, if the sample is large and random enough, the results can reflect some truth.

But the problem lies in that “if.” Not letting respondents handle the phone is largely to prevent them from seeing the entire questionnaire. What if they see later questions like “Are you satisfied with community policing?” or “How effective is the anti-crime campaign?"—might that unconsciously “polish” their earlier answers? Or, seeing the question options, might they be led in a certain direction? They need respondents’ “first reactions,” not answers that are pondered or self-censored. Having the interviewer ask each question helps control this “information contamination.”

Additionally, handing the phone to respondents could lead to issues—like Old T feeling the questions were too many and bothersome, rushing through them just to finish, which could seriously skew the results.

Are Foreign Polls Scientific?

Old T recalls reading news last year that Guangzhou is the only city in China allowing foreign investment in social survey agencies. At the time, I found it surprising that there would be barriers in this field. But a few months ago, while researching the “Corruption Perceptions Index” report, Old T suddenly realized there might be a need to restrict foreign agencies in social surveying.

Interested readers can check out Old T’s earlier article What Is the Global Corruption Perceptions Index?.

Here are a few key points. Simply put, that corruption index, despite its prestigious appearance, is just a pile of secondhand data, and almost every source is questionable. Some surveys draw conclusions from a few hundred people in China’s 1.4 billion population, while the same survey polls thousands in tiny countries with populations of just tens of thousands. Some surveys show identical response data across a dozen countries at different development stages, completely ignoring socio-cultural and governance differences. Some statistical methods clearly involve manipulation, widening the gap between Western and Southern nations. Not to mention, many are funded by USAID-directed organizations—it’s less about public opinion and more a tool for targeted smearing.

Old T isn’t saying foreign polls are worthless—they’ve developed earlier and have their own logic and rules. But often, those logics and rules serve specific interests, becoming tools to manipulate public opinion.

In comparison, domestic surveys today are more about channels for listening to public opinion—the difference is clear.

As for the recent online buzz about some schools conducting satisfaction surveys with only “very satisfied” and “satisfied” as options, Old T won’t rant further here—we all know what’s up.