Recently, Old T came across an academic paper shared by netizens in several WeChat groups titled “The Possibility of a Large-Scale Return Migration Wave of Elderly Migrant Workers and the Challenges of Rural Reemployment.” The paper points out that as the cohort born during the second baby boom (1962–1970) after the founding of the People’s Republic of China gradually reaches retirement age, a significant proportion of them, especially those who worked away from their hometowns, are not covered by urban employee pension insurance. Upon reaching retirement age, they often receive only the basic urban-rural resident pension insurance, which amounts to just over 200 yuan per month. These individuals, who have already returned, are currently returning, or are about to return “permanently,” find themselves in a dilemma due to the transformation of rural livelihoods and the reduction of non-agricultural employment opportunities. This situation also poses an unprecedented challenge for rural society.

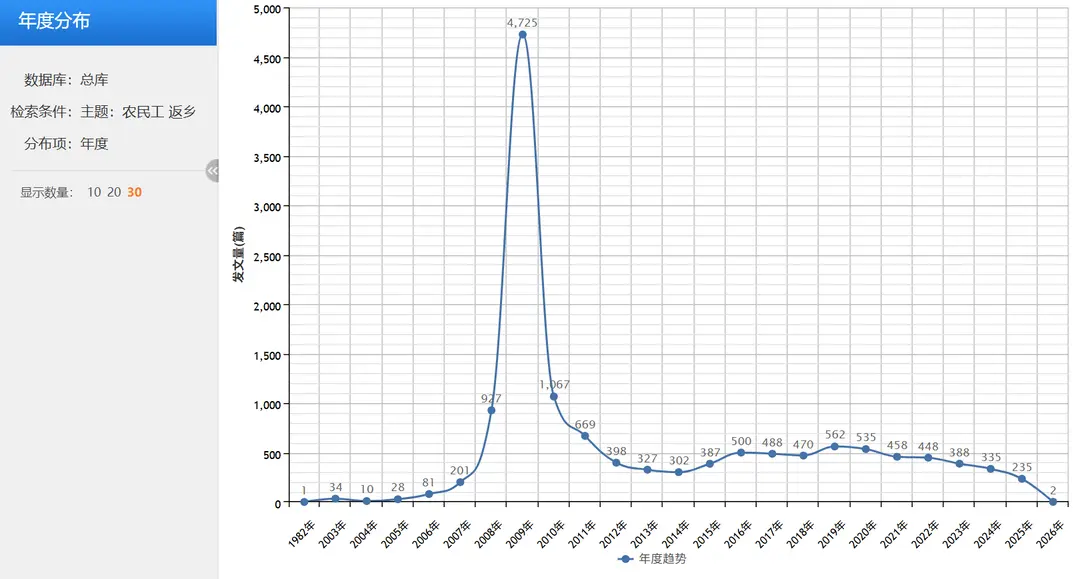

Over the past 30 years, there has been considerable research on the issue of migrant workers returning home. A simple search on CNKI reveals that related studies peaked in 2009, with over 4,700 articles mentioning the topic that year. Since then, the issue has remained a hot topic in academia, with hundreds of related studies published annually. However, the situation in 2009 was primarily influenced by the 2008 economic crisis and did not last long. Some scholars argue that it was merely “cyclical return migration,” as many of those who “returned” at the time had not yet reached retirement age. They temporarily returned to rural areas due to economic cycles but later returned to urban jobs with the onset of large-scale infrastructure development.

By 2026, hundreds of millions of migrant workers have reached another milestone in their lives. As they age, their physical strength declines, and they lack stable social security in cities, they are ultimately forced to “return home permanently.” Academia has already noted this trend, summarizing it as the “large-scale return migration wave of elderly migrant workers.” This is not an emotional judgment but a result driven by demographic structure, social security systems, and economic conditions. In particular, the generation of migrant workers born during the second baby boom mentioned earlier is now collectively entering old age.

The question is: What happens after they return?

I. An Approaching Reality

Imagine working in a city for 20 to 30 years, building skyscrapers, or assembling countless mobile phones, only to find in your fifties that the city no longer needs your physical labor. With incomplete social security and a pension of only 240 yuan per month (the national average is around 240–250 yuan), covering rent and food in the city becomes a challenge. What would you choose? Many can only pack their bags and return home.

This reality is not an isolated case. According to the latest data, in 2022, migrant workers aged 50 and above accounted for over 30% of the total. By 2026, this group is facing large-scale return migration. Economic downturns and intensified employment competition have made them the first to be “optimized” out of the workforce. Rural areas should be a fallback, but today’s countryside is no longer what it used to be. With agricultural mechanization and fewer non-agricultural opportunities, returning elderly individuals often find themselves with little to do.

Why is this “approaching”? Because the peak of population aging has arrived. Without prior planning, this return migration wave could pose certain risks. It’s like a high-speed train suddenly slowing down—how should the passengers be accommodated?

II. Why “Returning Home” Is Almost Inevitable

For many elderly migrant workers, whether to return home is not a matter of free choice.

On the one hand, the urban system is not friendly to older workers. Many jobs have explicit age thresholds, and issues such as labor contracts, social security contributions, and employment risks push older migrant workers to the margins. For example, many factories explicitly require applicants to be “under 45 years old.” Beyond that age, they can only find temporary work or security jobs, with unstable incomes and difficulties in maintaining social security.

On the other hand, the level of urban-rural resident pension insurance is relatively low. In 2026, the national minimum basic pension standard is 163 yuan per month, with many areas actually paying around 240 yuan. This is almost insufficient to sustain a basic life in the city but barely constitutes the minimum condition for “survival back home.” In villages, living costs are lower, and they can grow some vegetables on their own land, making ends meet.

Additionally, the current economic downturn and fierce employment competition often make elderly migrant workers the first to be squeezed out. The aftermath of the pandemic and the relocation of manufacturing have led many middle-aged and elderly individuals to view returning home as the “only feasible path” in reality. Think about it: if you earn 2,000 yuan per month in the city but spend 1,000 yuan on rent and utilities, is what’s left enough for retirement? Returning home at least means having your own house.

III. Returning to the Countryside, Only to Find “Farming Is No Longer the Way Out”

A fact often overlooked is that today’s countryside is no longer a traditional agrarian society.

In many areas, agriculture has become highly mechanized and scaled, reducing the labor absorption capacity of family farming. After land transfers, returning farmers may “have land” but not enough labor opportunities. In the past, a few acres of land could support a family; now, large agricultural machinery can complete a day’s work in an hour, leaving small farmers as mere spectators.

At the same time, non-agricultural employment opportunities in rural areas are decreasing. The decline of township enterprises, the outflow of young people, and the limited scale of the service sector have left many returning elderly migrant workers in an awkward situation. On the one hand, they are older, their physical strength is waning, and agriculture no longer requires as much labor due to mechanization. On the other hand, non-agricultural jobs in rural areas are scarce and often favor younger people. Moreover, even if they return to the city, they lack a stable foothold, leaving them in a “no-win situation.”

The result is that returning home for retirement often reveals that the rural economy is also transforming, and the old ways no longer work.

A Frequently Misunderstood but Essential Clarification

When Old T saw the aforementioned article in WeChat groups, many naturally focused the discussion on questions like “Why are rural pensions so low?” Frankly, the gap in pension security levels between urban and rural areas, as well as between different systems, has long existed and remains significant at this stage. For many rural families, the idea that “the elderly should retire peacefully” is not an emotional demand but a traditional logic of life based on intergenerational support, land security, and family responsibility.

It is precisely for this reason that debates often arise in society about whether the elderly should continue to work. One concern is whether emphasizing “reemployment” too heavily could be interpreted as evading the reality of low pensions or even misconstrued as shifting the responsibility that should be borne by the system back onto individuals and families.

It must be emphasized that discussing employment pathways for returning elderly individuals does not deny the importance of improving pension security, nor does it advocate replacing social security with labor. On the contrary, it is precisely under the premise that pension security still needs continuous improvement and cannot be fully achieved overnight that providing low-risk, non-compulsory participation channels for willing and capable elderly individuals becomes an unavoidable practical issue.

In other words, the core of the “elderly migrant workers returning home” issue is not “whether the elderly should continue to work” but whether there is a path that neither denies the value of a peaceful retirement nor leaves returning elderly individuals with the sole option of “idleness or marginalization” before pension security fully covers all needs.

IV. How Developed Countries Address “Aging + Return Migration”

Due to China’s late start in reform and opening up, this is the first time the country is facing such a large-scale return migration of elderly labor in such a short period. However, historically, some developed countries have experienced similar stages. After entering deep aging, these countries did not simply exclude the elderly from the social system. Instead, they created numerous low-intensity, low-threshold, non-competitive participation opportunities through institutional design.

Japan’s “Silver Human Resources Center” model is a typical example. Local governments organize people aged 60 and above to engage in community cleaning,绿化维护 (greening maintenance), care assistance, agricultural sorting, and other tasks, avoiding heavy physical labor and emphasizing proximity and flexible hours. Some European countries rely more on community economies and cooperative systems, allowing the elderly to participate in public services, community care, and small-scale production. The goal of these positions is not efficiency maximization but social stability and dignity maintenance.

The commonality of these experiences lies not in “making the elderly continue to work” but in: first, no longer relying on land itself to absorb elderly labor after agricultural modernization; second, positioning the elderly as participating members of society rather than passive dependents; and third, reducing participation barriers through institutions and technology instead of leaving risks entirely to individuals.

The essence of such models is to provide a non-confrontational social participation mechanism alongside pension security.

V. The Realistic Space for “Participation” for Returning Elderly Under Changing Technological Conditions

Unlike in the past, China’s current technological environment is significantly reducing the binding of labor to location and physical strength. This provides returning elderly migrant workers with choices that did not exist before.

The first category includes platform-based, remote basic labor, such as e-commerce customer service, content moderation, information labeling, and data entry. These positions require short training periods, controllable work rhythms, and rely less on physical strength, emphasizing responsibility and stability—making them suitable for middle-aged and elderly groups.

The second category consists of auxiliary positions formed around rural logistics, e-commerce, and public services, including sorting, packaging, site management, government service代办 (proxy services), and smart device assistance. These jobs rely on existing systems and emphasize familiarity with local conditions, making them suitable for absorbing people at the township level.

The third category involves轻资产 (light-asset) small-scale services and production, such as preliminary processing of agricultural products,生活维修 (life repairs),经验型咨询 (experience-based consulting), and community care. These activities do not aim for expansion but use digital tools to reduce transaction and organizational costs, making them sustainable.

It is important to note that the significance of these pathways lies not in the income level of individual positions but in their ability to absorb people on a large scale and their flexibility in participation. For many returning elderly individuals, even a few hundred yuan in supplementary income per month can significantly alleviate financial pressure and, more importantly, prevent marginalization.

VI. Conclusion: Providing a Viable Path for Those Who “Can Return”

As a social “reservoir” and “stabilizer,” rural areas need proactive maintenance rather than passive waiting. The return migration wave of elderly migrant workers is already a reality. The key is not whether they return but whether they can live with dignity after returning. In this process, improving pension security remains a long-term goal. However, during this transitional phase, preserving diverse, non-compulsory participation pathways for returning elderly individuals is equally important for social stability. Only by ensuring that the elderly have a home to return to, meaningful activities to engage in, and a safety net of security can this generation enjoy their later years in peace and inject new vitality into rural revitalization.